LATAM Market Growth, Personified

MercadoLibre stock analysis: the Latin American super compounder

Hey investors 👋,

MercadoLibre is one of my portfolio’s most resilient compounders—a stock I’ve been wanting to cover for a while, and one I’m finally excited to share with you all, in detail. Much like Amazon, MercadoLibre is an e-commerce leader, sometimes called “the Amazon of Latin America.” Unlike Amazon, MercadoLibre leads in the fintech space which includes debt and payments.

MercadoLibre is an outstanding quality compounder with competent management, growing fundamentals at a rate well-within J. Nicholas territory, and returning +1,620.76% over the past 10 years. Question is: Is there any chance you can yield similar returns nowadays, at today’s prices?

Business model & analysis

MercadoLibre, Inc. is an Argentine company headquartered in Montevideo, Uruguay that operates an online e-commerce marketplace platform, as well as a fintech and credit business (payment processing, digital wallets, and lending).

The name of the company literally translates to “free market.”

Revenue breakdown

MercadoLibre earns its revenue from two categories (Commerce and Fintech) that can be further broken down into five key segments (%’s as of Q1 2025):

Commerce Services (45.5% of revenue): Final-value fees (sale commissions), advertising fees (MercadoAds), logistics/third-party delivery fees (MercadoEnvios), as well as listing, storage or any fees on the MercadoLibre marketplace.

Financial Services & Income (24.8% of revenue): Payment processing fees (on and off Mercado’s payment or commerce platform(s), debit card fees, asset management fees (balances of its interest accounts), insurance revenue, etc.

Credit Revenues (19.3% of revenue): Interest income on commissions and loans (MercadoCrédito; the debt business), and credit card transactions revenue.

Commerce Product Sales (10.1% of revenue): First-party sales from products owned and distributed by MercadoLibre itself.

Fintech Product Sales (0.2% of revenue): Sales of Mercado Pago POS devices (point-of-sale hardware).

Consolidated, the “Commerce” segments of the business make up 55.6% of revenue, while “Fintech” makes up 44.4%.

Revenue breakdown by country:

Brazil (51.9% of revenue)

Argentina (20.6% of revenue)

Mexico (23.3% of revenue)

Other (4.2% of revenue)

Business model

“Like Amazon, PayPal, Shopify and American Express, wrapped into one.”

This would be how I describe the totality of MercadoLibre’s business.

Controversial statement? Maybe. But I can promise: it won’t be once you finish reading this post today (or tomorrow, it’s pretty long).

MercadoLibre is a special company. A terrific business. It deserves a special mix of compliments for this. Put down your knives, because yes, Mercado isn’t nearly reaching the best of each of those aforementioned businesses combined; it’s just very similar in operational nature. Mercado has the seamlessness of an online retail/e-commerce foundation (like Shopify and Amazon), logistics scale (like Amazon), the ecosystem leverage of big tech (like Amazon), the payment processing business (like Shopify and PayPal), and massive underwriting advantages (like American Express and Shopify).

By business model, Mercado is an asset-light technology company. Its foundational business is e-commerce, and third-party seller fees continue to be its largest revenue source as a per cent of total revenue, by a lead of ~21 basis points compared to its next largest source (which is payment processing fees), as seen above. In fact, 90% of all the revenue Mercado takes in is, by definition, capital-light in nature. However, in practice, Mercado doesn’t fully operate in the same low-capital-intensity style. There is a small nuance, and that’s with logistics.

In the online e-commerce space, a business has three options when deciding on logistics (how the packages will end up in the consumer’s hands):

You leave the problem to the seller (the eBay way; the default way).

Sellers are required to pay for the labels, handle drop-offs, and are personally liable for shipping delays or defects. You host the marketplace and take fees per sale, that’s it. Purely digital-based.

You operate a logistics service option for your seller base where you earn small, small fees but use 3PL (third-party) services and partnerships to carry out the service (the Shopify way).

You don’t own any logistics infrastructure, or the burden of high capital costs like the first option. You allow the option, but you outsource the work. This is again a fully digital commerce model. All Shopify does is host a platform, but they created a way to earn more fees while keeping the capital intensity away.

You fully own the logistics process and infrastructure

All of the warehouses, the entire delivery process—everything (the Amazon way). You take on a capital-heavy business burden.

Every e-commerce site a new seller sells on will be defaulted to the eBay way when it comes to logistics. If you own a Shopify store or start selling on Amazon (or MercadoLibre), you’re liable for the shipping process. It’s only by choice that you would want to enrol in the in-house distribution services those particular sites offer (but those choices do matter). And MercadoLibre’s logistics service? It’s not any of the remaining options aside from the default. It’s a mix. But it’s rapidly venturing towards the Amazon option.

Unlike Amazon in the U.S., MercadoLibre doesn’t fully own its infrastructure in LATAM—at least not at the relative same scale.

In Latin America, there just wasn’t any infrastructure foundation when MercadoLibre came into the market at all. If MercadoLibre wanted to replicate Amazon, they had to start with no foundation and build it up themselves. Fast-forward a decade and a bit from the launch of its logistics platform in 2013 (MercadoEnvios), and as of now, MercadoLibre has the largest, most advanced e-commerce logistics network in Latin America (specifically in Brazil, which is its main market). MercadoLibre created a LATAM-specific distribution network that can sustain scale. They don’t outright own all of their distribution centres, or their cargo planes, or their delivery vans. Most of them they lease.

So, this is the nuance of saying MercadoLibre is a “capital-light business,” because while it’s true by definition, it actually holds weight of capital intensity as a consequence of logistics, in practice. Like Amazon. As of recently, the company is expected to spend $5 billion towards expanding its warehouses in Brazil alone, not accounting for fintech or any other logistics expenses.

But I digress.

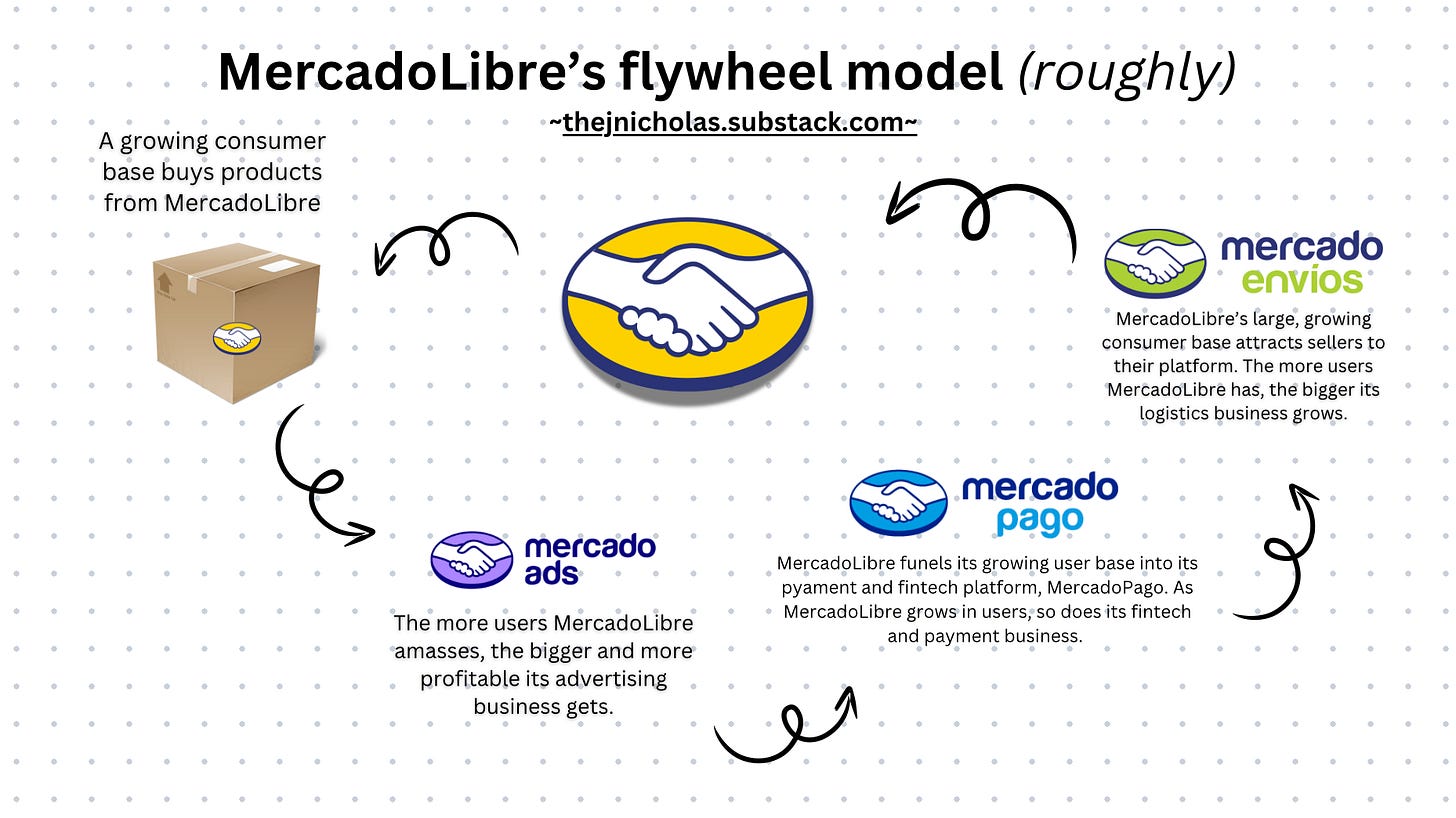

MercadoLibre, like all major e-commerce businesses, operates with a flywheel model, allowing it to leverage its marketplace advantage and brand towards more high-margin businesses related to the core customer. Amazon, as the core example, used its reach on e-commerce and brand to start a subscription for better deals and benefits (which led to Prime Video and Amazon Music and Alexa and FireTV and Ring), launching a third-party logistics service, advertising service, and starting AWS, to name a few—all core drivers of profitability for the company given the low-margin nature of retail.

MercadoLibre went the exact same direction. The company also went the subscription route with Meli+ (includes free shipping, cashback on MercadoPago credit cards, and discounted or free access to streaming services like Disney+ with ads), and launched its third-party logistics service and an advertising service for its sellers. But given that the Latin American consumer doesn’t have a large amount of discretionary spending, they can’t always buy stuff from MercadoLibre and pay a subscription. It might not be the best long-term strategy, even with the many benefits. And so, MercadoLibre also has a way to earn revenue when these consumers aren’t shopping. That’s where MercadoPago comes in (the payments business), and in the same vein, MercadoCredito (the debt business).

Side note: Since Meli+ isn’t reported separately by Mercado, this won’t be a critical aspect of today’s analysis. I don’t mention it again throughout the report.

On the consumer side, MercadoLibre locks in the market audience by offering low prices as a benefit of its scale, with relatively quick shipping across its major markets, while offering easy payment solutions and cheap debt to further boost revenue and availability to purchase. A consumer goes to MercadoLibre, buys an item, sees the option to sign up for MercadoPago, and eventually gets aware of MercadoCredito. That would be the simplified consumer flywheel. MercadoLibre earns revenue everywhere in this process—even on a fragile consumer.

On the seller side, MercadoLibre gives sellers the largest marketplace in Latin America, the largest logistics service in Latin America, and the largest payment solution in Latin America, to sell their stuff effectively. MercadoLibre also has a Shopify competitor product (MercadoShop) for sellers wanting to host their own store, which is integrated into their logistics network and payments. However, while this is undoubtedly part of MercadoLibre’s flywheel and goal of achieving an end-to-end seller solution—much like Shopify and Amazon combined—

(This Shopify competitor has not been working well, though. In fact, MercadoShop’s active store count has been declining since the end of 2023 as they lose share to Tiendanube (a leader in LATAM small- and medium-sized seller e-commerce, where most are going), Shopify, and WooCommerce. Retention is the problem here. This does have potential given Mercado’s logistics and payments integration, but the execution doesn’t seem to be working as shown by the data. That, or the product is garbage. I don’t live in LATAM, sadly, so I can’t test this theory. I also won’t continue to mention this in the analysis or business flywheel going forward because of that.)

The flywheel for MercadoLibre goes as follows: consumers buy something from MercadoLibre. Since MercadoLibre has the benefits of scale, it has the largest variety of products and sellers, and its integration with the largest logistics network in LATAM has made its shipping times the best in the industry (which is great for sellers). Over time, being the objective “best” e-commerce site in the LATAM market (based on pricing and shipping times) has led to high word of mouth, and now brand name recognition. This has led to more sellers joining, which leads to more consumers buying, which leads to MercadoAds becoming a big slice of the business as sellers try to gain share from the sales, and so forth.

As consumers continue to use MercadoLibre (the marketplace), they are introduced in indirect ways to Mercado’s payment platform, MercadoPago. This helps ease the checkout process, and because of MercadoPago’s scale as a result of the integration with MercadoLibre (all sales on the site are dealt through MercadoPago), this payment platform is also one of the best peer-to-peer money transfer platforms in the LATAM market. Once the consumer is intertwined with these services and has built trust (which happens if they use MercadoLibre anyway), it feels like a no-brainer to use MercadoCredito in the case of short-term loans.

And in a market like LATAM, which is very untrusting, financial trust is everything. MercadoLibre has done what Apple, Google, Shopify (at a smaller, imperfect scale), and Amazon have done: they’ve created a closed-loop experience. By controlling the payment (Pago), the product discovery (Libre), the delivery (Envíos), and the lending (Crédito), the consumer has very little reason to go elsewhere. Actually, scratch that—they have absolutely no reason to go elsewhere because most people are using Mercado and its products.

With this Hercules grip on the market, as I’d say, switching costs are incredibly high. Network effects compound on top, plus an already existing market share lead on every business segment. And this advantage only grows stronger as comfort and history build with the consumer. Additionally, since Mercado now knows how much the user spends, what they buy and how often, their payment reliability and volume (and income and sales trends for sellers), they can underwrite with better accuracy than a bank for their leading credit platform.

Flywheel: consumer buys from MercadoLibre, a platform “most in LATAM” use because of its selection, relatively low cost, and fast shipping —> more sellers flock to MercadoLibre because of this scale, using Mercado’s logistics and ads platforms to stay competitive on the marketplace —> consumers then come into contact with MercadoPago —> MercadoCredito is now the obvious choice for any consumer credit needs because of the trust built throughout this process.

I’m sure some consumers get caught in this flywheel from any part of the process and not from the e-commerce marketplace. For example, MercadoPago and MercadoCredito are at scale to the point where, for some consumers, these businesses could be the first time they have ever interacted with Mercado. It doesn’t have to start from the e-commerce marketplace business. But for the most part, that flywheel above is how it goes in terms of consumer retention. This is the business model.

Earning its revenue

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The J. Nicholas to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.