Understanding Quality Compounders

Breaking down key metrics of high-quality stocks

Hindsight Alert: This post is outdated. My book How to Analyze Stocks is officially published and it includes my real breakdown and understanding of these topics. This post does not reflect my current thoughts.

Hey investors 👋,

Welcome to today’s Deep Dive.

This is the third part of my free 5-part Deep Dive series on how to analyze stocks, in preparation for the release of my upcoming eBook, How to Analyze Stocks. This eBook is my full framework and process. It will teach you how to find, analyze, research, value, and profit from high-quality stocks. Premium subscribers will receive this eBook for free.

This eBook will teach you how, and my paid analyses will do it for you.

At this point, you’ve learned how to find and research the business of high-quality stocks. Now, it’s time to dive deeper (pun intended) into arguably the most enjoyable aspect of research: financial analysis, compounding returns, and the attributes that show how great a business truly is.

Let’s get into it. (14 min read)

Today at a glance:

A deeper look at the financials

The compounding formula

A deeper look at the financials

So far in this preview series, we’ve gone over a few things:

How to find a high-quality stock

How to research a high-quality stock

What to look for in a high-quality stock

Assuming you’re following this series with a stock you’re currently researching, you should have found and researched a company with consistent financials, great management, and decent capital allocation strategies. Yet, while you might now be an absolute master at the qualitative side of the business, there’s much we still haven’t covered on the quantitative side. We went over the value of consistency in financials, but that has been it. But now it’s time we learn about specific financial analysis in this issue; the groundwork for distinguishing a profitable investment from the herd, after spotting consistency.

Margins

Let me give you a scenario. Imagine you own a bakery. This bakery, like most of the world in 2025, sells its products with a subscription. Whatever works, works, you say. But anyway, your bakery is hugely popular in Toronto where you operate, and because of the subscription, your revenue almost never dips. Year after year, from word of mouth and some Google Ads here and there, your customer base grows, and with it, your consistent revenue.

Growth is amazing! Business is booming. And you decide it’s time to open more stores. You sign a 3-year lease on your next space in the same area, but operational costs increase and profits subside. Revenue is still very consistent and booming quarter after quarter, but your profits don’t keep up. Cash flow depletes, and to continue running, you need to drown your business in debt.

This, my friends, is what I’ll call the rotten pig analogy when it comes to businesses. This may be a bit morbid, so skip over if you don’t enjoy the comparison: Pigs on a farm generally are fed to fatten and eventually get slaughtered for consumption. With a business, the consistency of revenue is like the food for your pigs. You need it to keep things going. Without input, there’s no output. Same can be said for the pig farm. Now, unless there’s an output from the input (i.e., profit generated from the revenue or selling the meat of the pig as a result of the feeding), the business fails. If you continue to feed your pigs more and more without any means, the pig will eventually get hurt. Maybe the stomach gets ruptured—who knows. The theme is, when an animal gets hurt internally, it dies. And when it dies, the meat gets bad. The pig itself doesn’t need to die for the meat to go bad inside; if there’s decay on the inside, that will happen anyway.

No grocery store wants to buy rotten pig meat.

And no investor should want to buy a rotten pig business—a business where the outside revenue figures are outstanding, but the inside profits or cash flow metrics are rotting in front of your eyes. (Very similar to Tesla1 at the moment, but even then the revenue outlook is very poor.)

Eventually, if a business produces no output from the input, the business dies. Either from rising debt due to costs, or rising costs due to failing profit—even lowering costs can kill the business in this instance because, I don’t know, what if your Google Ads are what keep the revenue going? That’s an operational cost you can’t afford, but need. Thus comes the downward spiral.

Take CoStar, for example. A very pristine revenue-generation business. Absurdly consistent. Over 10% revenue growth for the past 10-20 years.

Though the problem with this company is that virtually every other financial fundamental has driven off a cliff in recent quarters. Free cash flow, as an instance:

I do not know much about the company or its issues. I am not a shareholder and have no understanding of the business. Maybe, just maybe, this is a one-time occurrence. However, these sorts of companies—when you ultimately find with research that they fit the rotten pig analogy—you must stay away from.

Now, there is an exception to this rule, and that would be growth (in other words, rushing the pig to surgery)—and we’ll get into that later. But in order to avoid buying one of these rotten businesses, we need to talk about margins.

I look at four margins when I go about analyzing financials. Mostly because I’m a very simple man, and I hate overcomplication.

And if you are a paid subscriber to this newsletter who reads my very detailed, award-winning (not really) stock reports, you might already know what these margins are.

Gross margin

The profit from the sale of a product after subtracting the costs of the product itself (cost of goods sold, or COGS).

Operating margin

The profit after subtracting the gross margin from operating expenses; the expenses to keep the lights on: payroll, baking supplies, utilities, lease payments, marketing, etc.

Profit (net) margin

Revenue minus all expenses of the business—taxes, operating expenses, and COGS. Even non-operational expenses like depreciation (which, back to the bakery analogy, is an effect of your lease to open the new store).

FCF margin

What percentage of revenue is converted into free cash flow—dollars the company produces and can actually use.

TL;DR: Gross margin shows pricing power, operating margin shows efficiency, net margin shows proof of concept, and FCF margin shows profitability.

My use cases/definitions for using only these four margins (and what attributes I look for when researching):

A gross margin of over 40%, which tells me the business has incredible pricing power (since it can mark up its products at almost double the flat cost).

An operating margin of minimally less than gross margin (30% is my ideal), which shows me that sales don’t require a lot of operational effort. A higher margin can tell me there’s a lot of organic sales and that the business is productive and efficient.

A net margin of 15-20%, which shows me that things can work. Not a top-of-mind metric for me, but important because it shows proof of concept and that a business isn’t losing its grip. (It’s, by GAAP measures, very profitable.)

An FCF margin of 15-20% or more, which shows me the business is truly profitable inherently—beyond earnings (which don’t paint a fair picture for most companies)—and can invest and grow and/or return capital. More on the importance of how it invests this cash below. Something to note about FCF: because of the way the formula works for calculating it, FCF can be harsh on capex-heavy companies like automakers or those investing heavily in growth, like many of the cloud computing giants at the time of writing (Amazon, Google, Microsoft).

For a real-world example to compare, here’s Amazon—my largest stock position (as of Q4 2024):

Gross margin: 47.34%

Operating margin: 11.29%

Net margin: 10.65%

FCF margin: 5.15%

Now, you may wonder why my largest position contradicts what I look for in the businesses I wish to own. And that’s where yet another exception comes in. First of all, gross margin is on point here. However, the other metrics, you’ll notice, are behind. But the thing about margins is that they can change quickly. If Amazon wanted to, it has the levers to pull itself into an outstanding financial position on the margin front—but it chooses not to, yet. With time, these margins will get better and refine, and even when they don’t—as of now—slowly but surely, every quarter Amazon’s margins continue to improve (aside from FCF margin, which, as we discussed, is affected by high capex). Qualitatively, Amazon is pristine, and quantitatively, this will follow.

Now, it’s time we talk about debt.

Debt

Finally, we get to debt—one of those controversial aspects of financial analysis. First, let me clarify, if you didn’t already know: debt is not a bad thing by itself. As I used in the above analogy, debt is only a problem if mismanaged. If you own a house, you probably have or had a mortgage at some point. If you have a credit card and collect rewards… well, hopefully you pay it off at the end of the month.

In both of these instances, no one would consider debt a problem. And that’s because in both of these instances, debt is being used appropriately. This would be educated debt management.

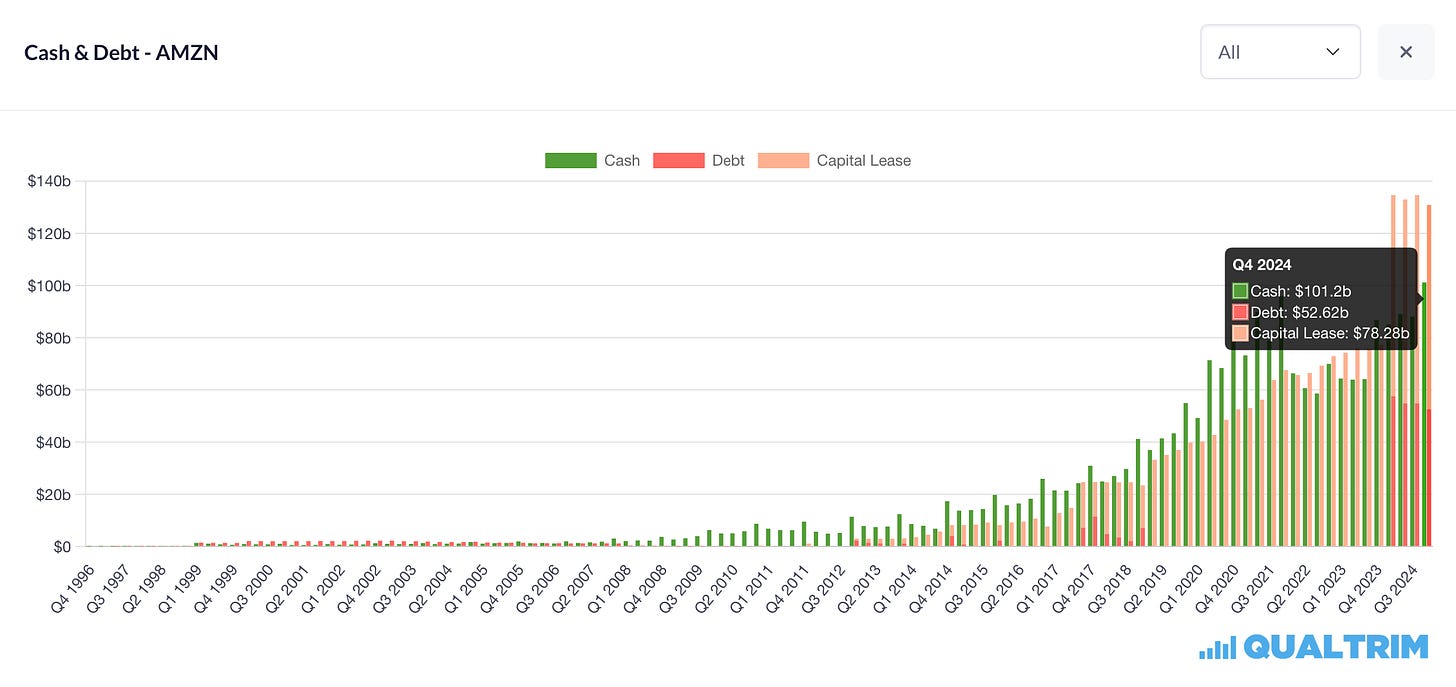

I hear it thrown around a lot (not really) how Amazon has a lot of debt. And while this is absolutely true, it does not mean it is a problem. Let’s take a look at Amazon’s balance sheet:

What we see is (as of Q4 2024):

Cash: $101.2 billion

Debt: $52.62 billion

Capital Lease (found as Lease Liabilities on the balance sheet or otherwise) (basically a mortgage for physical assets—in this case most likely warehouses and/or data centres—but where the company owns the asset it loans against at the end of the loan’s term): $78.28 billion

Now, all public companies are required to show their rate of debt in their regular filings. Most of the detailed information is in the annual reports, as we went over in the last part of this series. For Amazon, their current rate on debt as of year-end 2024 (blended) is ~3.5%–4%.

As long as Amazon’s operating cash flow (OCF) growth is sustainably and consistently growing higher than this percentage (which it is) (~36% YoY), the company has no debt problem. (FCF growth is usually more accurate here. However, in the case of companies like Amazon, who deflate their true FCF due to disproportionately high capex investments, OCF is the best alternative.)

Also, if Amazon—or any company—has enough current capital to cover the total cost of all its long-term obligations instantly (like Amazon does: $134 billion combined cash and annual TTM FCF as of Q4 2024, opposed to $131 billion in debt and obligations (including capital leases), then debt is even less of a problem.

Now, you do not want a company leveraged to the moon, so there is one ratio I love to use in combination with the aforementioned details, and that is debt-to-EBITDA. By my standards, a debt-to-EBITDA at or below 2 is great to aim for. In Amazon’s case, this number is 1.06—meaning with about one year of core earnings, all of Amazon’s debt can be erased.

“But Jacob, why do you use profit margin instead of EBITDA margin and not debt-to-earnings instead of debt-to-EBITDA? You hypocrite!”

First, ouch.

Second, fair question.

And the answer is simple: GAAP earnings take into account non-operational measures; EBITDA does not. When looking at debt—opposed to “yeah, this business can business pretty good” profitability—EBITDA works best because it shows the operational strength of the business if it were to pay off its obligations. That’s what makes it better, in my eyes, for this use case. Hence the reason it is part of my financial analysis.

Margins and debt are awesome, but this finally leads us to the most crucial aspect of financial analysis: What makes the business compound—its return on invested capital; ROIC.

The compounding formula

ROIC is one of those heavily underrated aspects of people’s research process, but an aspect that’s so crucial for long-term success. Think of it as the brain and the heart for your strategy. There’s no getting away from it. Without it, you simultaneously have no metaphorical blood circulation and no cognitive abilities. In every instance, your investments are dead meat.

ROIC is just a fancy metric that tells you how much a company makes in profit for every dollar invested (after taxes). It’s calculated by dividing total invested capital by net operating profit (after taxes). By itself, ROIC is nothing of major value, but with adequate context, it can make or break the quality of the business you wish to analyze.

For any company wishing to grow, they need to reinvest.

More specifically, they need to reinvest at a return above their cost of capital.

A company’s cost of capital would be WACC (weighted average cost of capital), which is calculated by combining the cost of equity and the after-tax cost of debt, weighted by how much of each the company uses to finance its operations. (Don’t worry to memorize this though—I myself had to look up that formula definition. (It’s simply something to know.)

Good news is, both ROIC and WACC (like most publicly traded businesses) are widely calculated across the web. I personally use Gurufocus (free) to view this data, but there are many sources you can go to see these metrics without wanting to calculate them yourself at the time—though doing it yourself would, of course, give you the most accurate and up-to-date results every single time.

ROIC and WACC are important because each serves a purpose in the formula of value creation, which is the compounding formula.

Again, let’s use Amazon (as of Q4 2024):

ROIC (TTM): 14.62%

WACC: 12.44%

Spread: +2.18%

With the businesses you analyze, when you subtract these two numbers, it should be positive. If it’s positive, the company is actively creating shareholder value—intrinsic value for the dollars it invests. If it’s negative, the business is actively eroding value for shareholders. Keep in mind, this metric is completely separate from financials—it’s solely for the dollars that are reinvested. Also know that this spread amount is not the annual rate at which Amazon (or whichever company you analyze) is growing its intrinsic value. That would lead us to the final calculation: Amazon’s reinvestment rate and rate of shareholder growth.

Profitable reinvestment

Now, to preface, most companies do not report maintenance capex and growth capex separately on the financial statements. Amazon is not an exception to this rule. Therefore, when we go about measuring the total investment into growth, we will be taking total capex into account. This is not a bad thing. In fact, it makes things more conservative, since we as the investor are assuming every dollar of capex has to make a return for shareholders. And if it turns out to be a decent return even with this assumption, that’s extremely bullish.

To calculate, take the total amount of OCF of a company in the past year, and divide it by the total amount of capex in the same timeframe. This gives you the reinvestment rate, which in Amazon’s case is 71.6%. (Yes, you read that right—Amazon is reinvesting nearly 72% of its total cash flow.) And to calculate the rate of return from these investments? Multiply it by ROIC.

0.716 × 0.1462 = 0.105 (10.5%)

Therefore, the rate at which Amazon’s new investments are compounding is a little less than 11%. This tells me what Amazon is getting back for every dollar it’s choosing to keep and reinvest instead of returning to me as a shareholder. That’s the compounding rate of the Amazon machine.

To add, every quarter, at this moment in time, ROIC and rate of reinvestment continue to grow, and Amazon management continues to be confident in the outlook of the investments. And Amazon, being so massively profitable (and growing), is able to provide for this growth and then some. This, among a massive list of reasons, is why Amazon is my largest position.

If you don’t own Amazon, this should still be an amazing framework to base your research on—no matter the company you’re looking at.

And that marks the end of this week’s Deep Dive. See you next week for another paid stock report, where I do all of this research and analysis for you on a quality stock that you can apply to your portfolio. Thank you to all the current paid subscribers and patrons for you support.

Thanks for reading. All the best.

Note: Some people may have different criteria for a quality business, and that’s perfectly fine. Investing is an art, not a science. It just requires some practice to get your style. You first need to know the basics, then continue developing the craft until you’re comfortable enough to consider yourself an artist. The same goes for investing. I’m not a dividend investor, value investor, or growth investor. I’d say I follow GARP (Growth at a Reasonable Price) and do so pretty well (a mix of value and growth), but my style is unique to me, and that’s what I write about. It will also evolve with time.

Thank you for reading, partner. If you enjoyed today’s issue, feel free to share it with friends and family. I’ve placed a button below for you to do so (right underneath the paid membership line (see what I did there).

All the best,

Jacob

All of my links here.

My best work is members-only. Don’t miss out on exclusive posts, insights and benefits—upgrade today and join the community.

Please don’t hurt me, Elon.

Do not trust WACC.

Wacc is greatly dependent on Beta.

Beta is dependent on daily stock quoted price fluctuation, aka volatility.

A lot of info, saved it to look into it deeply later and it’s perfect because I’m looking at Amazon to invest as well!