Assessing Quality Compounders

How to build a thesis, weight your portfolio, deploy cash, and know when to sell a stock

Hindsight Alert: This post is outdated. My book How to Analyze Stocks is officially published and it includes my real breakdown and understanding of these topics. This post does not reflect my current thoughts.

Hey investor 👋,

Welcome to today’s Deep Dive.

This is the final part of my free 5-part Deep Dive series on how to analyze stocks… in preparation for the release of my upcoming eBook, How to Analyze Stocks. This eBook is my full framework and process formatted in one cozy place. It will teach you how to find, analyze, research, value, and profit from high-quality stocks. Premium subscribers will receive this eBook for free.

This eBook will teach you how, and my paid analyses will do it for you.

At this point, you’ve learned everything about analyzing a stock. How to find, how to research, how to understand, and how to value a stock. But now, it’s time to wrap things up by sharing with you how to manage the holding when you own it: It’s time to learn how to build a thesis from your research, how to weigh your portfolio by conviction, how to deploy cash, and when to sell.

Let’s get into it. (20 min read)

Today at a glance:

Building a thesis

Managing a portfolio of conviction

When to sell

Building a thesis

Building a thesis is simple. There’s no formula or special DCF to calculate it. All it is, is a brief summary of your research you’ve carried out thus far.

Here’s an example:

[Stock/company] is a [describe what it does], with [e.g., “wide network moat,” “high teens growth,” etc.], trading at [“a fair price ($. per share)”]. I believe the stock can generate [X]% annual returns over [Y] years due to [XYZ].

It doesn’t even have to look like this either. This is just the example, and depending on what you think is valuable to include in your thesis—and what you got out of your research—this could change. In fact, here’s what one of my theses looks like for comparison:

“In the next 5 years, Uber and its core business segments in ridesharing and food delivery will continue to experience 14-17% revenue growth as the market increases according to global and secular trends (e.g., much fewer people getting driver’s licenses), and as operational leverage continues pushing for margin expansion. Uber will inevitably start decelerating to “low teens growth” (10-13%) as market share saturates and margin expansion/operational leverage hits near the peak, near the middle or end of this timeframe.

In the decades later, Uber will become a core distribution partner with companies manufacturing or producing the technology for commercial autonomous vehicles using their unparalleled experience and their network for millions of people to create a no-brainer hosting platform to these providers. Uber will earn fees from each of these companies’ rides, and overtime if succeeded, will turn the company into an even higher margin business as Uber drivers won’t be needed anymore, or at a smaller scale. Uber Ads and Uber One could still be in operation with AV partnerships, and Uber Eats will continue to grow with secular trends.”

I know some people who have extremely short or extremely long theses; I know some people who use voice notes to log their thesis instead of writing it down. I don’t know these people personally, but I’m sure they’re out there.

Point is: People are different. Companies are different too. The way you write your thesis could change depending on these two factors alone.

If you’ve been following along throughout this series, you should already have a great understanding of the research process and how to understand and examine a business (or the business you wish to own). I repeat: a thesis is just a brief summary of your research. Everyone will (and should) have a different definition of what that consists of.

For me, having a thesis is a glance-easy way1 of understanding my research that I can quickly look at whenever. It’s also a positive mental hassle to be able to condense hours of research into a few sentences or a paragraph, and it helps strengthen your conviction (which we’ll get to below). In some ways, a thesis is your way of being able to explain your research to others. So goes the quote by Albert Einstein:

“If you can’t explain it to a child, you don’t understand it yourself.”

The rule of thumb is: If you cannot support your thesis in a given argument or conversation surrounding the company you researched, you either (1) don’t know enough (no one person ever does, but sometimes one could miss important details), or (2) don’t understand what you know.

For the first issue, the way to solve it is to research what you don’t understand.

It’s not hard to do so, but it’s discouraging to have a conversation or read someone’s writing on a company you just researched and not fully understand what they’re talking about because you clearly have a lack of knowledge on the subject.

My hardest research thus far was with Brookfield. I have the benefit of writing my research down and sharing it on this blog, and I do so for every company I wish to analyze. But with Brookfield—even in my paid analysis on it—I learned, two or three months later, that I didn’t understand the insurance business. After I finished my research, I still wasn’t finished my research. I just thought, “Oh, insurance, I know that.”

Long story short: I learned Brookfield’s insurance arm is annuities, not traditional insurance as I originally understood. And thanks to talking with folks like you in the Discord, and reading a couple of threads on Twitter on the topic, I now fully understand the Brookfield insurance business (one of the fastest-growing segments of Brookfield). (This is when you clap.)

I’ve been in this situation with possibly every company I’ve ever researched. Have I still made money? Do I continue to understand my businesses in great detail? The answer is yes to both of those questions. You will too, and having these “lapses of understanding” only helps further strengthen your thesis.

There’s only downside apparent when you believe you know everything. But there’s unlimited upside when you admit you don’t.

For the second issue—not understanding what you know (ergo, not understanding your research)—upgrade to paid and read my easy-to-read, well-researched stock repor- just kidding (wink, wink?).

The quote unquote best way to fix this can be tricky because people learn differently, and it depends on the problem causing the misunderstanding.

The only two causes for misunderstanding your understanding are: (1) you don’t know enough (which stems back to what we just answered above), or (2) you just don’t understand what it is you’re researching. Which is normal, especially for more complex businesses, but a problem that needs to be solved.

If it’s a complexity or “big language” issue (which this problem normally is):

Write down everything you personally understand from your research (even if it’s wrong) into a summarized thesis.

Re-read your research (if you’ve written it down; if not, look back at your sources and take it slow to understand better).

Re-evaluate this thesis you wrote down.

In case you need it, use an online thesaurus to help with definitions. By that I mean Google Search, Gemini, or ChatGPT to help with understanding complexity.

Constantly dumbing down “what you don’t know” to understand it better (ie “explain like I’m five”) will dumb you down too, so do so with caution.

Drink your whiskey with an acknowledgment of your limits, so to speak. Whiskey being LLMs and online thesauruses, and drinking being the act of dumbing things down. You didn’t learn how to speak your mother tongue by reading a dictionary. It was all through context. If you want to be as fluent in research as possible, try to avoid dumbing things down whenever possible.

It won’t kill you to look up a definition of course, but there are limits, and everyone has a different “tolerance to alcohol.”

The good news is: the more you carry out research, the less you’ll need to define anything. Finance jargon has a cap, and at some point once you know most of it, you’ll understand the majority.

Your “finance jargon comprehension conviction” will increase, or so I’ve found. Like that right there, that was jargon.

But speaking of conviction:

Managing a portfolio of conviction

No, you can’t just buy holdings and let each naturally weight itself over time through returns or gains. You need to be intentional with how you buy so you can control how your portfolio looks when those gains come into play.

I’m a fan of concentrated portfolios. That does not mean I’m a fan of 50% yolo weightings into one single stock without sufficient reason.

“I’m a fan of concentrated portfolios” means I’m a fan of having only a few names (stocks) make up the lion’s share of a given portfolio, weighted by conviction and understood by research.

Conviction is important in your portfolio balancing decisions because businesses are different. Even if every holding of yours meets the same stradegy-wide growth criteria, your conviction might vary between all of them. What if one of them is John Deere and the other is Amazon?

Your portfolio and its weightings should always follow conviction. In the case of downturns, you’ll not only survive better emotionally when your highest conviction stocks drag down your portfolio, but you’ll be much more comfortable to invest your money into businesses you’re comfortable with. And if you’re doing it right, it also lowers the chance of panic selling.

Conviction is not a way to weight “good” or “bad” companies. Conviction already assumes you’ve previously measured the quality of the business, its valuation upside, growth potential, and risk relative to your specific time horizon. Conviction is simply how you feel when you feel the research and understanding of what you own.

An example: if you were given the choice to drive manual, but you’re more comfortable driving automatic—even though you know how to drive both—you’re still more likely to choose automatic, while acknowledging that manual has its advantages (like fuel efficiency). Both are cars you can drive; only one is the car you’ll drive much more often. Stocks in your portfolio are the same.

If you’re more comfortable driving automatic—more comfortable in your understanding and research of a certain company over another—then put more money into that company and weight it more heavily.

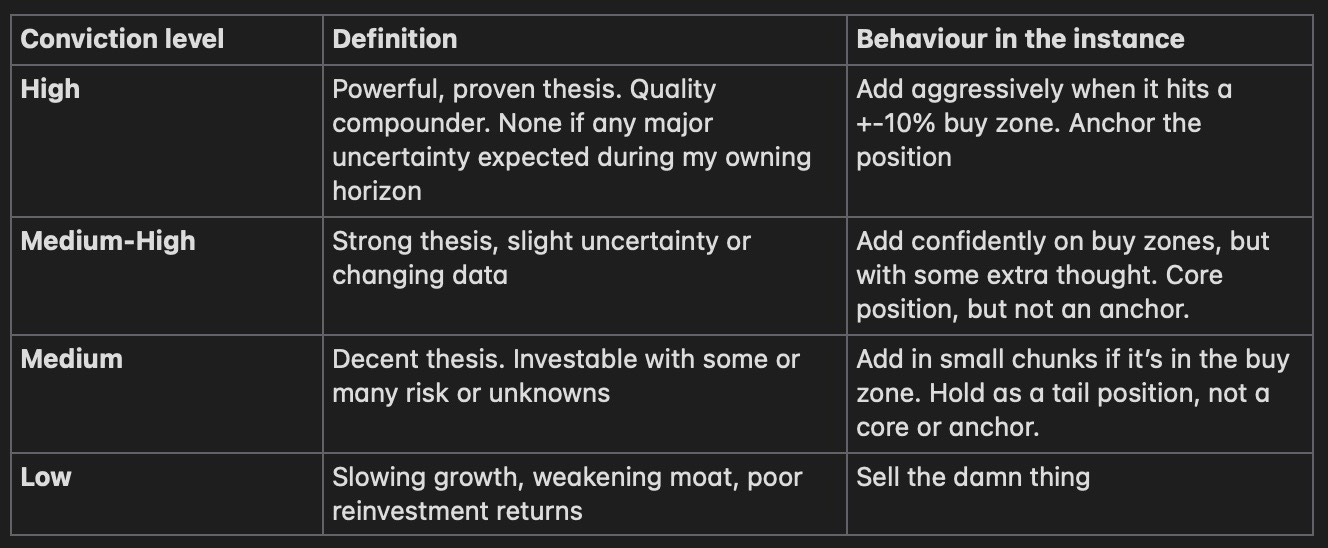

How heavily? Well, that’s subjective too. But here’s a chart:

More context for the chart:

An “anchor” high-conviction holding deserves up to 15% weighting in a given portfolio.

A “core” medium-high-conviction holding deserves up to 12.5% weighting in a given portfolio, and

A “tail” medium-conviction holding deserves up to 8% weighting in a given portfolio.

You should never have a “low” conviction holding in your portfolio. Chances are it won’t harm you assuming it’s low weighted, but if it doesn’t serve a purpose, it shouldn’t deserve a spot. This is also why I’m not a fan of “watcher positions.” They won’t harm you, but they’re a useless concept and use up capital.

This chart shows how I weight my holdings, which is done by using a conviction framework from low to high. It’s a simple chart, and self explanatory. It’s also a new understanding of my strategy that I decided to take on because of an experience I had with a holding of mine, American Express. It was unironically from this experience that helped me create this weighting framework, but that’s a story for another day.

To summarize, the simple idea for my entire investment framework is to buy when stocks go below fair value. But in order, it goes:

Weight business, per conviction, in portfolio

Sound fair enough?2

It’s a simple framework as-is, including if you’re starting out and have just built your portfolio for the first time. But there are many questions to ask depending on where you’re at, particularly if you’re an intermediate or more experienced investor reading this and wondering:

“Okay, so I have a portfolio. I’ve weighted by conviction with my current holdings. But what if I inevitably make more money in the future and would like to add to my portfolio?”

This is crucial, so thank you for asking such a question, dear reader.

First, you re-evaluate valuation. This should be done on a trailing twelve-month basis every quarter with earnings. It’s not a must, but if you have recurring paycheques or capital (as one does) it’s best to have updated data. Only when your company drops more than 10% below your estimated fair value should you consider it in buying territory. (PS: This is only my rule of thumb, and it can absolutely vary depending on the company in question3.)

Second, analyze if your positions are “underweighted” or “overweighted” to find which companies you can take out of the “adding to” pile.

If a position is high conviction but low weighting, then it’s underweight. If a position is low conviction—or on the lower end—but has a high weighting in your portfolio, then it’s overweight.

If a holding is overweight, you don’t add. An overweighted position can be trimmed or left alone, depending on your risk tolerance. It doesn’t have to match the flat weighting caps shown above if your conviction evolves alongside the rise in the holding’s weighting.

If a holding is underweight and undervalued by your desired margin (again, mine is 10% minimum, with exceptions), then that is the company (or companies) you should be buying with your cash, but only up to a weighting in your portfolio (before gains) that matches the conviction caps, with exceptions.

Here’s an example scenario with this conviction-weighting framework in action, because sorry, that must’ve been all over the place:

John is starting a portfolio with five companies: Amazon, Google, Shopify, Brookfield, and American Express. He’s researched all of these companies and has found that each is trading at a fair price he deems aligned within his goals. He has $100,000 in cash exactly, and splits this in his portfolio between his researched companies according to his conviction.

He buys:

$24,590 of Amazon (giving it a 15% weighting as an anchor position, reflecting his high conviction)

$24,590 of Google (giving it a 15% weighting as an anchor position as well, reflecting his high conviction)

$20,490 of Shopify (giving it a 12.5% weighting as a core position as well, reflecting his medium-high conviction)

$20,490 of Brookfield (giving it a 12.5% weighting as yet another core position, reflecting his medium-high conviction)

$9,840 of Amex (giving it a 6% weighting as a tail position, reflecting his medium conviction)

One month later, John receives his paycheque of $5,000 (yes, he’s paid monthly). He would like to invest this cash, so he deposits it into his RBC Investing account. Lucky for him, the market has gone up exponentially in that one month, and his portfolio makeup has changed:

Amazon: $46,721, 30.34% weighting (overweight)

Google: $40,574, 26.35% weighting (overweight)

Shopify: $29,711, 19.30% weighting (overweight)

Brookfield: $26,637, 17.30% weighting (overweight)

Amex: $10,332, 6.71% weighting (underweight)

John’s conviction hasn’t changed for any of these positions, but the prices of the positions have gotten more expensive. The only two companies that are still within his reasonable buy zone are Brookfield and Amex.

John hasn’t added any money to his portfolio in a month. Compounding is doing its work, but it’s also messing up his portfolio distribution.

How does John know what to do with his new cash if his positions have already gone over his holding caps (e.g., Amazon, a high-conviction holding, is over 20%—more than the 15% threshold, and so on)?

Well, of John’s five positions, 4 out of 5 are “overweight” in his portfolio based on the conviction-weighting framework above. Only 1 out of the 5 is “underweight,” and it happens to be in a buy zone. That 1 position is Amex, and John’s conviction in Amex is still “medium,” so his max weighting he could have is 8% of his portfolio. John has $5,000 in cash, and getting Amex to 8% weighting would take $2,159, so he places the order. This solves the overweight problem by diluting some of the larger positions and allows John to continue to invest.

John’s portfolio now looks like this:

Amazon: $46,721, 29.93% weighting (overweight)

Google: $40,574, 25.98% weighting (overweight)

Shopify: $29,711, 19.03% weighting (overweight)

Brookfield: $26,637, 17.06% weighting (overweight)

Amex: $12,491, 8.00% weighting (neutral)

Right now, John could trim his overweight positions and take that cash to open a new position in another compounder he’s researched that’s trading at a fair price, or he could re-evaluate conviction and decide that certain holdings are fine to go above a certain threshold because his risk tolerance can stand it; his conviction can sustain it going above the “guidelines.”

With trimming, there’s a chance you dilute your returns. With substantially overweighting a position, there’s also a chance you dilute your returns. For most decisions, it’s just best to let your winners run because it’s hard to predict which way it’ll go. And so, John takes his remaining cash and puts it into short term treasuries, corporate bonds, or a high-yield savings account, weighting4 until his companies dip into a reasonable buying opportunity (or if he decides to add another position to his portfolio).

If you’re “out of room” to add to a position based on this conviction framework, cash becomes your position.

You don’t need to constantly be adding to your companies.

You won’t “miss out” on returns for taking it slow and rational.

You don’t have to rush to add to your positions with every paycheque.

Take your time, buy at a fair price, and weight in your portfolio according to conviction. Then let compounding do its work and your thesis succeed until your company doesn’t produce your desired return… then sell and reallocate:

When to sell

Most investors like ourselves focus most of their time on picking the right stocks to buy and everything else we’ve covered in this series so far, but what everyone forgets is the simple fact about selling: you’ll need to do it eventually. I believe it was Peter Lynch who said (paraphrasing) a stock doesn’t care that you own it.

You’re here to make money, and making money comes from owning businesses that can produce the returns you want. There’s no need to own said businesses (stocks) once they stop providing those returns.

And so, knowing when to sell is, in theory, grounded in that logic as well:

When the growth of the business falls to a level you believe will not correlate well with the returns you want,

A weakening competitive advantage,

Terrible management with poor direction and clarity (this really only matters if the management is making a detrimental impact on the business or growth, otherwise it’s premature because an idiot can run an amazing business and chances are the business will continue to operate well in the short term).

Valuation should never be the sole consideration when you sell out of a stock. Only when paired with one of the other three factors above should it be included in your sell rationale.

Let’s use Tesla and Shopify as examples for this:

Tesla at the moment, trades at roughly 3 times the market in terms of earnings valuation. (The 12-month forward multiple for the S&P 500 is 20x, compared to Tesla’s 61x). This means Tesla investors are betting Tesla will grow its earnings three times the market over the next year. That’s what’s being priced in at the current valuation. (Note: I don’t use P/E often, but it’s very well known on this app so it’s easier to use as a reference here)

The market is expected to grow earnings at 8% over the next year, so here’s what the math says: Tesla needs 24% earnings growth from now until next year to justify its valuation today.

Tesla’s current growth aspects? Negative earnings growth, stagnant revenue, and stagnant cash flows. The business aspects? Losing market share to Chinese automakers, and declining sales in many foreign markets due to Musk’s politics.

Sure, there are arguments to be made about robotaxi and everything, but this is not presently having any impact on the company’s fundamentals. So that is irrelevant until it becomes something. Based on these metrics alone, Tesla is a stock that if I owned, I would be selling.

It just is overpriced.

Growth is nowhere near my portfolio goals of 12-15% annually, the business is far from high-quality, management is uncertain and has very rarely met its promises, and its valuation only paired with these other concerns, makes outsized returns from today’s price, very unlikely. Plus, Tesla is in the process of compressing margins due to lower demand for their products.

This is an example where valuation plays a larger role in indicating if you should sell a company. However, there are times where a valuation is “justified”—like with Shopify.

Shopify’s competitive advantage unlike Tesla, is growing. As I covered in my analysis a while back. Earnings (and revenue and cash flows) are growing speedily and consistently, its management is not uncertain or overly political to the extent where it damages growth or operations, and valuation is not egregious.

Shopify’s forward P/E is roughly 50, or about 2.5x the market. The market is pricing in much less growth than it is for Tesla. And currently as of the last 12 months: Shopify has grown its earnings at ~100%+, and is expected to grow earnings at around 20-30% for the next five years. Shopify still has years ahead to expand margins, so this could be even higher.

Again, the market is expected to grow at 8% next year. If the market is pricing Shopify at 2.5x the market, and Shopify is expected to grow at 2.5x the market (which it is), then today’s multiple could be justified.

The basic rule of thumb for selling right is to not baselessly sell because of valuation. Take context into the question. These two dramatically different examples should help you in finding that for yourself and your businesses (stocks). People ignore stocks exclusively because of valuation and even sell because of price—without proper context! This leads to loss. In fact, more people lose money in the market from selling than they do from buying.

Look at Bill Ackman for example. Or Terry Smith. Both billionaire investors. One sold Neflix too early after one bad quarter, while the other held onto an extremely overpriced PayPal for too long. Both lost money because they didn’t sell at the right time. Selling is just as important as buying.

And look at you! Awesome sauce. You now know the basis of selling. But don’t go away just yet. I’m not done with you. Let’s talk about price and cost basis. Which also plays a role in selling (or not selling).

Like I mentioned at the start, buying a stock is an important factor when selling. It seems backwards, but stick with me:

If you own Tesla at an average of $80 per share, you’re much less impacted by the company’s overpriced nature at the moment and even price movements/volatility.

When your cost basis is lower, you’re in a much better position for volatility. If you bought Tesla at $80, you might be able to ride out the current overvaluation, but someone who bought at $300 is much more exposed to that issue. Disproportionately.

You still inherit much of the business’s problems regardless of price (that’s not going to go away), but you’re now in a much better position than before simply because of the price you bought in. Future growth potential is much more valuable to you because you own the company at a much lower price.

At $80 per share, you’re holding Tesla at what would essentially be a 21x forward earnings multiple (basically the market average). (Tesla isn’t even growing at the pace of the market, so this is technically still overpriced, but assuming growth aspects, adequate research, and strong conviction, a holder at $80 is not in a bad position. Generally speaking.)

Then there’s Shopify. My personal average is CA$80 for this stock. Using the same math of P/E multiples, I’m essentially owning Shopify at a 29x forward earnings multiple. Meaning relative to the market average, I paid 1.45x times earnings for a company expected to grow 2.5x the market.

I don’t believe current buyers are being “ripped off” in any sense by buying Shopify today, but since I give myself a margin of safety by buying stocks at “discounts,” to their actual value, I and other investors with the same strategy have yet another advantage. I think Shopify is fairly valued as of this write-up, but where you can gain an advantage on a cost basis is from buying below fair value.

If a pack of strawberries is worth $15, I can buy them for $15 without much trouble. But if it drops to $10 with a coupon. You bet I’m using that coupon to buy those strawberries now. The same applies to stocks. For better value and returns, buy a stock at the best price possible. Learn about how to find that price in this post in the series, here.

Buy when stocks trade below their value, sell when they no longer justify their price. Never sell because of valuation, because if you bought at a fair price anyway, your cost basis will help you fight off absurd price movements.

In summary, research, build a thesis, buy a stock, weight by conviction, and don’t get attached.

Your best investment might already be in your portfolio.

—-

And that’s offically the end of this series. Thanks for reading, everyone, and thank you for the support throughout. If you haven’t already, upgrade to paid so you don’t miss out on any future premium stock analyses, as well as access to my eBook when it’s out, as well as the community Discord.

I hope to see you soon.

Cheerio, friend.

All of my links here.

For me, apparently “glance-easy” translates to: A 1920 historical business novel-equivalent word count.

This is a movie reference. If you successfully understand it, you’re awesome. You win nothing, but just know you’re awesome.

For example, a high multiple trading stock that rarely goes on dips. In this case you’d want to capitalize on it ASAP once it hits your fair value, opposed to waiting for this 10% threshold.

Pun intended (spelling error intended).

Very interesting. I suggest you to list your book on Amazon with the print on demand feature.

I'd like to buy a phisical copy when it will be finished;)

By the way, why you don't share your portfolio to your paid subs?

I think buy and sell Investing alerts will increase the appeal of your substack.